Ethiopia went through significant changes in 2018, starting with the resignation of Prime Minister Hailemariam Desalegn in February 2018, and his succession by Ethiopia’s first Oromo Prime Minister, Abiy Ahmed, in April 2018. Desalegn’s resignation was the result of popular anger and protests, especially among the country’s two largest ethnic groups, the Amhara and Oromo, over land ownership, political power and civil rights, and boundary disputes involving Addis Ababa that would displace thousands of Oromo farmers. From July 2016 until August 2017 the government imposed two successive six-month periods of state of emergency, giving it sweeping authorities in banning protests and arresting demonstrators. When Desalegn resigned in February 2018, the ruling coalition, the Ethiopian People’s Revolutionary Democratic Front (EPRDF), selected Abiy Ahmed to take over.

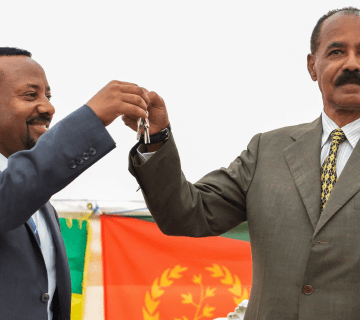

Abiy Ahmed belongs to the reformist wing of the EPRDF and has undertaken significant reforms since taking power. He has loosened restrictions on internet use, lifted much-criticized terrorist designations that had been applied to several opposition groups such as the Oromo Liberation Front (OLF), Ginbot 7 (G7), Ogaden National Liberation Front (ONLF),and the Tigray People’s Democratic Movement (TPDM), made peace with Eritrea, normalised relations with other Horn countries, shrunk cabinet to just 20 ministers (of which 10 are women), and set out to open the country’s economy. He has also promised free and fair elections by 2020.

In September 2018, the country experienced the backlash of these reforms. Ethnic clashes on the outskirts of Addis Ababa, in Burayu, and in Benishangul-Gumuz saw hundreds perish, numerous injured, and thousands arrested in the government’s crackdown. Amnesty International warned Ethiopia not to return to the time of arbitrary arrests and state of emergency, as was common under the old regime.

Such clashes, observers say, are normal in a country in transition.Abiy Ahmed’s rapid reforms are a thorn in the side for the ruling elite who hold positions of power and are benefiting from the status quo.Observers also argued that ruling elites instigate violence by paying gangs. A group of individuals of the Oromo community, interviewed by the Horn Institute, argued that the Amhara oriented Ginbot 7 did the killing in Burayu and tried to blame it on Oromo youth (Qe’ro) to instigate ‘Oromophobia’.Interviewees of the Amhara community on the other hand stated that it was Tigrayans who killed Oromo and blamed it on Amhara’s to create conflict between Amhara and Oromo. It is impossible to know the truth in this matter, but what becomes clear is a persistent tension between various ethnic groups. Going forward, Abiy Ahmed need to address these underlying tensions, ‘Oromophobia’, and ethnic violence, without resorting to violent crackdowns and arbitrary arrests. Additionally, opposition to Abiy’s reformist agenda from within his own coalition will be one of the key problems that need to be addressed.

Abiy Ahmed is generally viewed in positive light, despite newly surfaced tensions. Six recent reforms stand out: making peace with Eritrea, releasing political prisoners and allowing rebel movements to come back to Ethiopia, anti-corruption efforts, increased freedom of expression and movement, increased media freedom, and economic reforms. Surprisingly, the Oromo are sceptical of Abiy’s reforms and argue that he is not doing enough for the Oromo people. They often name four key issues to their struggle against oppression: land reforms, national language, the flag, and the future of Addis Ababa. To the Oromo, the current flag and the use of Amharic as a national language symbolize centuries of suppression, and their grievances over these issues have not been dealt with by Abiy. This may explain whyOLF increased in popularity. Abiyneeds to work closely with opposition groups to maintain peace and stability in Ethiopia, and prevent them from becoming spoilers. The government’s invitation of opposition groups back to Ethiopia this year might have been premature according to some.

Ethiopia’s economic sectoralso needs to be drastically reformed. Abiy needs to expand Ethiopia’s manufacturing, its tourism, and telecommunications, to create jobs for unemployed youth of rural populations whose livelihoods are threatened by persistent drought. An estimated two million people enter the work force each year, and Ethiopia’s economy will need to sustain its high growth to absorb this next generation of workers. Finally, Ethiopia also needs to look at other sources of donor financing instead of focusing predominantly on China. After years of borrowing, government debt is now nearly 60 percent of GDP, a situation the IMF has labelled ‘high risk’. Meanwhile, Ethiopia’s foreign exchange reserves have plummeted as export growth has faltered.

In any case, Abiy Ahmed is more popular in Ethiopia than any other Ethiopian leader over the last centuries, and his reforms demonstrate a willingness to change Ethiopia for good.