Tanzania’s plan to forcefully repatriate Burundian refugees sets a bad precedent for the African continent, and conflicts with the country’s legal obligations. This process should be stopped. The United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) (2019) estimates reveal that Tanzania hosts approximately 184,000 Burundian refugees, most of whom fled political violence in Burundi in 2015. Kangi Lugola, Tanzania’s Minister for Home Affairs has said that all Burundian refugees would be repatriated by December 2019. However, UNHCR has warned that conditions in Burundi are not conducive for the refugees to return to their country.

This repatriation exercise, which began on October 3, 2019, is being guided by an inter-governmental agreement signed on August 27, 2019, between the governments of Tanzania and Burundi. The agreement, however, failed to incorporate the views of other key stakeholders such as UNHCR, and the Office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights. (OHCHR).

2019 is the 50th anniversary of the adoption of the 1969 Organization of African Unity (OAU) Convention Governing the Specific Aspects of Refugee Problems in Africa. The African Union (AU) decided to mark the occasion by focusing on refugees, returnees and the internally displaced persons (IDPs) on its 32nd Summit where African leaders committed to finding durable solutions to forced displacement in Africa. Forceful repatriation, however, is not one of those solutions.

Why refugees are afraid to return

The Burundian government insists that the country is safe, peaceful, and stable. Nevertheless, reports from other entities indicate that this may not be the case. The International Criminal Court (ICC), for instance, estimates that more than 1,200 people have died in Burundi since 2015 as a result of clashes with security agencies and the state-controlled Imbonerakure militias.

On September 25, 2019, the Conference of Catholic Bishops of Burundi sent a letter to its churches expressing concerns over ongoing efforts by the ruling party to persecute perceived or real political opponents ahead of next year’s general elections. The bishops’ concerns were echoed by the UN human rights investigators who the Burundian government has denied access to the country.

Additionally, Burundi’s safety concerns were further shared by the South African Development Cooperation (SADC) in May 2019 while announcing its rejection of Burundi’s application to join the body. SADC said that the rejection was on the basis of Burundi’s unresolved democratic process and political instability.

These concerns suggest that the safety fears harboured by refugees maybe well-founded, and therefore, arguments by the Tanzanian and Burundian governments that the latter is safe for refugees’ return is neither here nor there.

Changing attitudes

As much as the implementation of this forceful repatriation is troubling, it has been in the offing. President Magufuli held talks with his Burundian counterpart in 2017 after which President Magufuli ordered a stop to a decades-old practice by previous governments to grant citizenship to Burundian refugees. According to him, this practice supports refugees’ refusal to go back home. Tanzania further stopped prima facie recognition of Burundi refugees and began considering each case individually. In 2018, Tanzania pulled out of the UN’s Comprehensive Refugee Response Framework citing a lack of international funding. This Framework is a declaration by countries to commit to respecting the human rights of refugees and migrants and to also support the countries that host them.

Burundian refugees have also complained publicly of mistreatment and deteriorating living conditions in the camps. The economic activities that they depended on for livelihood have been restricted since 2018. This includes the ban on the sale of food in the market and a reduction of the number of market days in the camps.

Tanzania’s legal obligations

Tanzania has both domestic and international legal obligations to guarantee the safety of not just Burundian but all refugees within its territory. As a signatory to the 1951 Convention relating to the Status of Refugees and its 1967 Optional Protocol, Tanzania committed to respecting the principle of non-refoulement and the rights afforded to all those whom it has granted refugee status.

The AU Convention Governing the Specific Aspects of Refugee Problems in Africa, which Tanzania also ratified, requires that the voluntary nature of repatriation should be respected at all times and in all cases and that no refugee shall be repatriated against his or her will. The Convention further demands that any appeal by a host country to refugees to return to their countries must be accompanied by assurances that the new circumstances prevailing in their country of origin enables them to return without risk and take up a normal and peaceful life.

Tanzania’s Refugee’s Act of 1998 and the National Refugee Policy provide for the respect of refugees rights, non-refoulement, and voluntary repatriation. Tanzania should, therefore, respect its legal obligations and join efforts by its peers in the AU to actualize the 2019 Summit’s theme of advocating for sustainable solutions to the challenges of displacement.

Sharing of the refugees

Whereas the Tanzanian government can cite the lack of financial capacity to sustain the continued presence of Burundian refugees, it has to be mindful that the imbalance in sharing of the refugees’ burden is a global phenomenon. It is estimated by the UNHCR that there are more than 70 million refugees and Internally Displaced Persons (IDPs) across the world that are in desperate need of humanitarian assistance. Unfortunately, this burden has largely been shouldered by the least financially-endowed countries that happen to be neighbors to affected countries.

Tanzania’s refugees’ burden, however, is not as severe as one would want to believe. According to the World Bank 2018 statistics, Tanzania’s Gross Domestic Product (GDP) was USD 57 billion and it hosts 326,000 refugees from the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC) and Burundi. Its neighbor Uganda, with a GDP of USD 28.5 billion in the same period, had more than 1.3 million refugees from South Sudan, DRC, and Burundi; while Kenya with a GDP of USD 87.9 billion, also in the same period, had more than 500,000 refugees from South Sudan and Somalia.

The responsibility to protect civilians who have fled violence is both a moral and political duty. Tanzania should, therefore, not adopt policies that are hostile towards refugees. The onus is now on the AU to express solidarity with the Burundian refugees and publicly remind Tanzanian government on the need to play by the rules or else this may embolden other countries on the continent to follow suit, thus threatening the safety of refugees.

Elvis Salano is a Research Assistant at the HORN Institute.

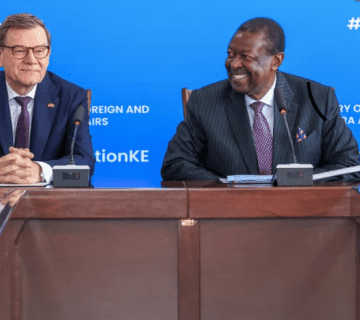

Photo: Tanzania Burundian Refugees Ferried to Safety (Photo Credit UNHCR)