The 2000 Arusha Agreement called for the two main ethnic groups – Hutu and Tutsi – to share power. It also put limitations and checks on the power of the executive, and limited the presidency to two terms. Burundian President Pierre Nkurunziza took power in 2005 after the twelve-year civil war ended. In 2015, he decided to stand for a third term in office, plunging the country in a political crisis and violating the Arusha Agreement. An attempted coup in the same year failed, resulting in a militaristic and oppressive state, and nearly half a million refugees. Despite promising political, democratic, and economic progress after 2005, recent decisions, policies and Supreme Court rulings have unraveled the fragile peace and growth in the country. It appears Nkurunziza, and his inner-circle, are keen on staying in power. The 2020 presidential elections are, therefore, at risk of becoming little more than an effort to gain international legitimacy and secure donor funding.

When Nkurunziza decided to stand for a third term in office in April 2015, the ruling party, CNDD-FDD (National Council for the Defense of Democracy–Forces for the Defense of Democracy), and the military split between those supporting his decision, and those opposing it. On May 13, 2015, Godefroid Niyombare, a Burundian military officer, announced on radio that Nkurunziza and his government had been dismissed. Two days later, on May 15, 2015, Chief of Staff, Lieutenant General Prime Niyongabo announced that the attempted coup had failed. In the aftermath of the coup, Nkurunziza and hardliners within the ruling party, embarked on a campaign of undoing the hard-won democratic and political freedoms, and disregarding the 2000 Arusha Agreement. In July 2015, Nkurunziza secured his third term through presidential elections, in which he garnered 70 per cent of the vote.

According to various Human Rights Watch reports, Nkurunziza, assisted by Evariste Ndayishimiye (the party secretary-general), Brigadier General Etienne Ntakarutimana (national intelligence), and Prime Niyongabo (army chief of staff), have purged opposition, harassed the media and journalists, violated human rights, and suppressed dissent within the ruling party. For example, on December 11, 2015, six months after the attempted coup, 87 people were killed in a single night in Bujumbura, allegedly by security forces and the party’s youth wing, Imbonerakure. Eyewitnesses told Associated Press that some of the dead had their hands tied behind their backs, and had been killed ‘execution style’.

The international community responded in 2016. The European Union (EU), which provided over half the government’s budget in 2016, stopped the direct aid and issued travel bans and financial sanctions by invoking Article 96. The Burundian economy was hit hard. In 2015, the CIA Factbook notes that foreign aid accounted for about 48 per cent of the economy. In 2016, that number had dropped to 33.5 per cent. Burundi’s GDP has yet to recover to ‘pre-unrest’ levels, as continued disengagement from the international community and donors restricts Burundi’s economic growth. It is worth noting that the Burundian refugee crisis was the world’s least funded refugee situation in 2018. Currently, amid a growing humanitarian crisis, nearly 1.8 million Burundians are at risk of food insecurity, according to the United Nations Refugee Agency.

Nkurunziza responded by cracking down on international NGOs in the country, harassing their workers and forcing organizations out of the country. The most notable incident was the February 2019 closure of the local United Nations Human Rights Office in the capital, Bujumbura. The government announced that the bureau was no longer justified to be in the country because Burundi had made sufficient progress with regards to human rights. This, in turn, resulted in even worse economic prospects. To cope with these setbacks, the government introduced the Tax Election Law in 2017 of BIF 2,000 (USD 1.10) per household, to be collected anytime and as often as needed. The Imbonerakure is tasked with collecting the tax, roughing up dissidents and civilians in the process. Additionally, in 2019, the Supreme Court ruled that assets belonging to opposition activists in exile and in prison be seized by the government. The ruling applies to 32 politicians, human rights activists and journalists, and is the latest step in a string of repressive and violating actions that seriously threaten the democratic process in 2020.

On May 17, 2018, Burundi held a constitutional referendum to remove presidential term limits as delineated in the Constitution of Burundi. On May 21, 2018, this adjustment was approved, allowing Nkurunziza to effectively stay in power until 2034. Two weeks later, in a surprise move, Nkurunziza announced that he will not run in the 2020 elections, and that he will step down after the elections. Just two months earlier, the ruling CNDD-FDD had bestowed the title of ‘Eternal Supreme Guide’ on him, claiming that he has been divinely appointed. It is highly unlikely that Nkurunziza will retreat from political life after 2020, raising suspicion that a ‘puppet’ from the ruling party might take his place, as was former president Joseph Kabila’s plan in the Democratic Republic of the Congo when his party fronted Emmanuel Shadary in the December 2018 elections.

Presidential elections are scheduled in 2020, but the country lacks financial resources to carry out the exercise. Burundi’s economy is heavily dependent on foreign aid and international donors, who in turn demand less repression on opposition members, journalists, rights activists and civilians from the Burundian government and the Imbonerakure. So far though, Nkurunziza has demonstrated little appetite for conducting free and fair general elections. Instead, as Human Rights Watch argues, Burundian authorities are hoping that if the world cannot see their abuses, they will simply disappear. To that extent, the United Nations Security Council has so far not introduced any sanctions, such as assets freezes or travel bans on any individual government official in Burundi. Additionally, the Inter-Burundi Dialogue, which began in 2014 under the leadership of the East African Community (EAC) has yielded little results, mostly due to Burundi’s refusal to join the sessions and the EAC members to press Nkurunziza to make concessions. This has allowed the ruling party to continue to unabatedly undo hard-won democratic and liberal gains after the civil war. Holding elections in such a volatile context runs the risk of becoming little more than a sham ‘legitimation’ effort, in which the government tries to gain international legitimacy through a shallow democratic exercise.

Using elections to legitimize an autocratic regime is not unique to Burundi. The approach has been adopted in several countries in the region, such as Uganda, Rwanda, Democratic Republic of the Congo, and Ethiopia. In Ethiopia, citizens stated that the ruling Ethiopian People’s Revolutionary Democratic Front (EPRDF) distributes food, seeds and money on the countryside to poor small-scale farmers who do not care who is in power as long as they get support, albeit temporary. In Rwanda’s latest presidential elections, the approval rate of President Kagame was unnaturally high, despite his existing popularity. The Guardian reported that Kagame garnered 99 per cent of the vote in the 2017 presidential elections, securing a third term in office just two years after a constitutional referendum removed constitutional presidential term limits (which in turn was passed by 98 per cent of the vote).

On the one hand, the ruling party shows little interest in conducting truly free and fair democratic elections in Burundi in 2020. On the other hand, a democratically elected government that represents the people, demonstrates good leadership, and upholds the 2000 Arusha Agreement is necessary to overcome Burundi’s many challenges. The question is whether the 2020 elections will actually deliver such a government, or whether they will be used to legitimize a government that is slowly but steadily unravelling the Arusha Agreement, and thereby diminishing the chances of lasting peace and stability in Burundi. Allowing Burundi to continue its democratic and liberal decline risks further escalation, not only for Burundi, but for the whole region, and should thus be prevented at all costs. The EAC and the UN Security Council should take a central role and pressure Nkurunziza and his inner-circle to allow for more independent media, ensure unlimited access for the UN Commission of Inquiry, prevent widespread human rights violations by its security services and youth wing, revise its oppressive and violent approach to political opposition, and conduct truly free and fair elections.

Jules Swinkels is a Research Fellow at the HORN Institute.

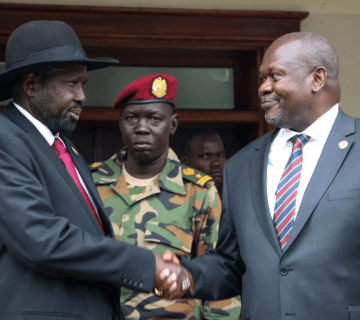

Photo: Burundi’s President Pierre Nkurunziza (centre) at celebrations marking the 53rd anniversary of the country’s independence at a stadium in Bujumbura on July 1st, 2015 (Photo Credit: Marco Longari/AFP/Getty Images)