The past decade has seen a burgeoning of relations between the Middle East and Africa. Notably, there has been a renewed interest among Middle Eastern countries to forge stronger relations in Africa. Not only have these relations taken centre-stage in the economic and political milieus but have also become prominent on the critical aspects of security and military. A-yet-to-be-published study by the HORN Institute on Middle East-Africa relations reveals that between 2010 and 2019, the total economic investment by five key Middle Eastern countries of the United Arab Emirates, Saudi Arabia, Qatar, Iran, and Turkey stood at an estimated 232.022 billion dollars. Out of this investment, almost 55 per cent came from the UAE.

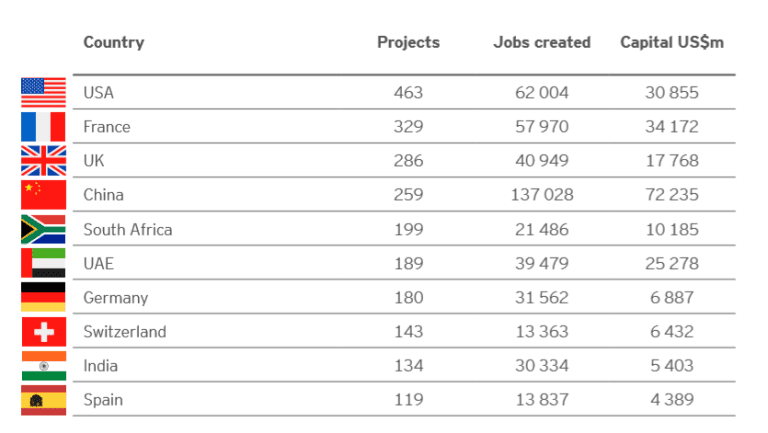

The figure below shows the largest investors by number of projects in Africa (2014 – 2018).

(Source: FDI Intelligence and EY Africa Attractiveness Report, 2019)

Geopolitical and Security Interactions

Besides the increasing economic investment and exchange between the two regions, there has also been a newfound strategic interest among countries from the Middle East and the Gulf to exert their geopolitical and security influence in Africa. Since 2015, countries such as Turkey, UAE, and Qatar, have expanded their involvement in Africa’s political and security landscape with intense activities mostly concentrated in the Horn of Africa. For instance, in 2018, the UAE and Saudi Arabia strongly encouraged and supported the rapprochement between Ethiopia and Eritrea. Although exact details of the nature of their role in the Ethio-Eritrean rapprochement remain unknown, their visible engagement was remarkable.

In 2017, Turkey completed its largest foreign military facility in Somalia valued at $ 50 million. The operation of the military base and its support to Somalia in the fight against al Shabab has amplified Turkey’s security influence in the Horn of Africa. Moreover, Turkey’s involvement in the restoration of the Suakin: an old Ottoman port town on Sudan’s Red Sea coast, has elicited debate in policy circles on whether Turkey harbours intentions to establish a Turkish military base in the Suakin Islands and how that might influence the security balance in the Red Sea arena.

The impetus by Middle Eastern countries to forge relations with countries in Africa appear to have been triggered by the double events of the 2011 Arab Uprising and the 2017 Gulf Crisis. These created animosities and geopolitical competition among Middle Eastern powers, offsetting a series of actions towards the redistribution of regional power and regime types, mainly by seeking alliances and influence in Africa. However, beyond the ideological refractions between the conservative Sunni monarchies led by Saudi Arabia and UAE, and the revolutionary Shi’a Iran, Turkey’s regional ambitions were aided by the rise of political Islamic movements such as the Muslim Brotherhood in Egypt. Notably, Turkey’s initiatives to establish military bases and port facilities in the Gulf of Aden, the Red Sea, and the Horn of Africa are seen as part of Ankara’s wider Africa strategy, in which President Recep Tayyip Erdogan has been keen to raise Turkey’s profile on the continent. For Qatar, the perceived hostile posture adopted by other gulf countries during the 2017 Gulf crisis increased its quest for new strategic alliances across the Red Sea in an attempt to survive the isolation and curb the influence of geo-political rivals.

Although a large part of the current Middle East-Africa relations is spurred by tensions within the GCC and the ensuing quest to redistribute power within the Middle East Region Security Complex (MERSC), the previous engagements with Africa were inspired by political openness and out of a clear business model. For example, as Fredrico Donelli and Brendon Cannon have highlighted, for more than a decade now, the UAE, through its state-owned corporation DP World, has invested in the development and management of Djibouti’s Berbera port based on country support through the infrastructural business investment model. Similarly, in 2005, Turkey launched a political agenda of openness toward Africa that was largely followed by a humanitarian and business model. However, this was short-lived when Turkey, in 2010 and 2011, took a more significant role in ‘mediating’ the Somali crisis thus becoming a major political actor and benefactor in the country.

UAE Deputy Prime Minister and Interior Minister Saif bin Zayed al-Nahyan at a past virtual security meeting. In 2018, the UAE and Saudi Arabia strongly supported the rapprochement between Ethiopia and Eritrea (Photo Credit: Reuters)

Impact

While the increasing Middle Eastern investments to the African continent have had some benefits, especially in the security and economic spheres, the asymmetrical nature of these relationships and the tendency to export Gulf problems to Africa, have brought about a conflicts in the region and heightened the risk of militarizing and destabilizing Africa, thereby negatively impacting development and human security across the continent. Somalia has been particularly negatively impacted by the competition of Middle Eastern powers seeking political and diplomatic forays in the country. As Neil Melvin writes in a 2019 SIPRI report, the tensions caused by the GCC internal dynamics and the realignments that followed in which a Qatari-Turkey and Saudi Arabia-UAE binaries were formed, “have under-cut the state-building project in Somalia through exacerbating existing domestic divisions as part of competitive proxy politics”. With Turkey and allies holding sway in Mogadishu, the ongoing ‘Gulf Cold war’ has increased the centre-periphery tensions in Somalia and thrown the region in a state of flux.

The demonstrated readiness to mediate some intra and interstate conflicts on the continent, the increased economic investment and a willingness to lead interfaith dialogues as exemplified by the United Arab Emirates’ hosting of the Pope in 2019, in the first ever visit by the Pontiff to the Gulf, has implications not just on the immediate peace and economic fortunes of the continent, but fundamentally helps in reducing interfaith distrust and religious schisms that have for long fanned passions of hate and violence across the continent, from Nigeria to the Central Africa Republic.

Sheikh Mohamed bin Zayed, Crown Prince of Abu Dhabi and Deputy Supreme Commander of the UAE Armed Forces (right) receives Pope Francis at the Presidential Airport in 2019. UAE has continued to promote interfaith dialogue and is keen on becoming a beacon of religious tolerance (Photo Credit: Ryan Carter/Ministry of Presidential Affairs)

In sum, challenges notwithstanding, the increasing economic, political, and security engagement of the Middle East and Africa shows that the relationship will likely endure. It is imperative therefore, that these engagements be sensitive to local interests and balanced to maximize the potential benefits in supporting development, security, and stability in Africa as well the Middle East.

Banner Photo: Sheikh Mohamed bin Zayed, Crown Prince and Deputy Supreme Commander of the Armed Forces with Abiy Ahmed, the Ethiopian prime minister, in Abu Dhabi in 2019 (Photo Credit: Ryan Carter/Ministry of Presidential Affairs)