South Sudan recently formed the long-anticipated unity government, and is now getting into the business of realizing the same – prioritizing appointment of key government officials, and settling matters relating to the militarization of the country, and boundaries of states. However, 25 years after the adoption of Beijing Declaration and Platform for Action on the Status of Women, and almost 20 years after the adoption of the landmark United Nations Security Council Resolution 1325 for increased involvement of Women in Peace and Security (WPS), South Sudan is still making the common but inexcusable mistake of keeping its women in the periphery of the country’s new socio-political reality. To avoid a return to yet another civil war, the conflict-afflicted young nation should also prioritize meaningful involvement and participation of women in nation-building. This will help to guarantee a unity government, and consolidate peace in the country, and region.

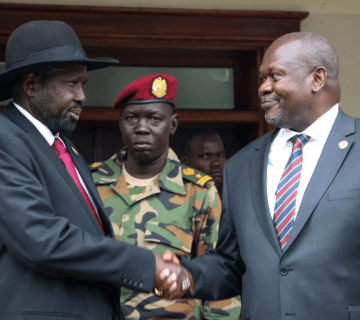

President Salva Kiir has already appointed several vice-presidents to his unity government, including former rebel leader Riek Machar, and Rebecca de Mabior (politician and wife of the then Sudan’s first vice-president, John Garang). Kiir and Machar are negotiating ministerial portfolios for the country, according to UN’s Secretary-General’s Special Representative, David Shearer. There are no indications that other women will be appointed to important government positions or the extent to which Kiir’s government will be inclusive. South Sudan is not the only one making this post-conflict reconstruction mistake. In Sudan, where women occupy only four of the 17 ministerial positions in the six-month-old government, women protested recently over lack of sufficient female representation; laws that discriminate against women; and lack of progress on women’s issues. Somalia has fared a little better than Sudan and South Sudan, and her women’s contribution to Somalia’s peace and stability has been acknowledged by the UN Secretary-General’s Special Representative for Somalia, James Swan.

In addition to discrimination, conflict experts have noted that women and girls, compared to men and boys, suffer disproportionately in armed conflict and post-conflict scenarios due to cultural perceptions on gendered roles. While targeting based on gender is unpleasant, women’s experiences give them a unique understanding of war-related injustices and increased appreciation for the value of peace. Thus, denying them a seat at the table of peace-reinforcing processes such as the negotiation of peace agreements, formation of government, planning of settlements for displaced persons, peacekeeping operations, and reconstruction of war-torn communities, curtails efforts to silence guns sustainably in post-conflict scenarios.

When Rwanda had the opportunity to do things differently, it embraced the challenge of adapting its 2003 Constitution to guarantee that her women will hold 30 per cent of elected positions. The result is a world record-breaking 61 per cent women representation in her parliament. The dividends of this investment include improved development outcomes that the country now enjoys. South Sudan and Sudan should take the opportunities that the formation of their nascent unity governments present them to model their post-conflict reconstruction efforts on Rwanda’s model.

The old-age schism of whether or not to include women in peace and security matters is largely driven by the still prevalent victim protection narrative. On the one hand, the proponents of exclusion insist that because ‘women are inherently weak,’ they should be protected from danger. They forget that some women participate in violent activities too, but also that, overall, women suffer more in armed conflict, and post-conflict settings; mostly in the hands of the ‘protecting’ males, compared to men. To complicate matters, fewer women, for reasons given, are directly available to take up leadership positions, in states or military in polarized, post-war environments. Thus, the process of deliberately seeking out and engaging women actively in leadership and nation-building can be time-consuming. The new government, in South Sudan, or Sudan, for example, may not be willing to allocate much time to affirmative action in the short term. However, the states will stand to lose more if they exclude women than if time is made for their inclusion at critical stages of nation-building.

Proponents of inclusion, on the other hand, argue that both men and women have the capacity to think and act for the greater good of their communities. Thus, considering women as being half-human, and discriminating against them dehumanizes them (women), and short-changes their communities of the potential gains of their participation. There is no denying that the political, social, and economic dynamics of South Sudan, and Sudan are dissimilar to Rwanda’s. Neither are Somalia, the Democratic Republic of Congo, or Central African Republic necessarily interested in forming unity governments, or allowing women to participate meaningfully in their societies simply because South Sudan and Rwanda, respectively, have done so. Yet, including women will lead to a reduction of incidents and prevalence of armed conflict and violence in these states.

To close the door to a return to civil war, the newest unity government in the region should prioritize the engagement of women, in the country and her diaspora, in addition to other priority areas such as the cantonment and unification of its 83,000 persons-strong national army. President Kiir should also seek meaningful participation of South Sudan’s women in the resettling of the more than two million South Sudanese nationals who may begin to return from neighboring countries in the coming months into regional states whose boundaries are still contested. Women should also be actively involved in the process of determining these boundaries. Once these boundaries are agreed upon, the new government should further endorse women to lead them. Going by the Rwandan example, taking this action will keep South Sudan firmly in her peace trajectory in the short, mid, and long terms.

Roselyne Omondi is the Associate Director, Research, the HORN Institute

Photo: President Kiir and his deputies after the swearing in ceremony at the State House (Photo Credit: Ministry ICT & Postal Services)