On September 12, 2018, South Sudanese President Salva Kiir and the main opposition leader Riek Machar, alongside leaders of other rebel factions, signed the Revitalised Agreement on the Resolution of Conflict in South Sudan (R-ARCSS) to end South Sudan’s most recent civil war. The agreement established a coalition government structure and reinstated Riek Machar as the Vice President (VP). In conjunction with the Khartoum Declaration Agreement (KDA) signed on June 27, 2018, the R-ARCSS included a permanent ceasefire, inclusive transitional security arrangements, and the formation of Revitalised Transitional Government of National Unity (RTGoNU) to hold office for a period of 36 months or until democratic elections are held.

However, with just a few weeks to November 12, 2019 – the end of the pre-transition period and the date set for the formation of the RTGoNU – the implementation of the peace deal is facing yet another stalemate. Machar, the main signatory to the peace deal, has said that the opposition – the Sudanese Peoples Liberation Movement-In Opposition (SPLM-IO) – will not be part of the transitional unity government, citing among other issues, the unfinished tasks of ensuring military integration of all fighting forces. Considering the ongoing stalemate and the need for sustainable peace in South Sudan, the international community – the United Nations (UN), African Union (AU), Inter-Governmental Authority on Development (IGAD) – and other state guarantors should work with South Sudan’s leaders to resolve the stalemate and fulfil all the outstanding issues before the RTGoNU can be instituted.

The Stalemate

On October 20, 2019, members of the United Nations Security Council (UNSC), Riek Machar and Lam Akol (leader of the South Sudan Opposition Alliance) visited Juba to hold high-level meetings with the incumbent government to asses the level of commitment for the implementation of the peace deal. While this visit was a good step toward fast-tracking the implementation of the peace deal, it did little to chart a way forward. In what appears as a move that will stymie the implementation of the peace deal, Riek Machar has stated that his party will boycott the formation of the RTGoNU. Machar claims that the mechanisms for transitional security arrangements agreed to in the R-ARCSS, especially, under Article 2.2.1, have not been implemented by the government. This includes arrangements for effective integration and unification of all necessary forces into the national army and consequent redeployment of jointly trained forces to provide security for RTGoNU officials and enhance national sovereignty.

Secondly, the lack of consensus on the number and boundaries of states puts excessive pressure on the agreement. The parties to the agreement have failed to agree on whether to uphold, review, or disband the boundaries of the 10 states that were recommended by the now-defunct Technical Boundary Commission (TBC) and the Independent Boundary Commission (IBC). Consensus is needed, however, so that the provisions can be integrated into the R-ARCSS and thus be used for legitimating the formation of the RTGoNU. Furthermore, and as SPLM-IO has decried in the statement published in The Sudan Tribune, the incumbent government has not released the necessary funds to facilitate the complete implementation of the obligations required for the formation and running of the first phase of the R-ARCSS.

Spoiling the Peace?

Edward Newman and Oliver Richmond, in their article The Impact of Spoilers on Peace Process and Peacebuilding have described the phenomenon of ‘spoilers’ and ‘spoiling’ in peacebuilding processes as, “groups and tactics that actively seek to hinder, delay or undermine conflict settlement through a variety of means and for a variety of motives”. By this definition, spoilers include parties, external or internal to the peace process, who use violence or other means, for example, withdrawal from, or obstruction to the peace process in order to achieve personal, political or other objectives other than the central aim of reaching a peaceful endgame. However, spoiling does not necessarily mean that the spoiler’(s) main aim is to destroy the peace process. In other instances, spoiling is used as a strategy to allow for adequate time for the parties to regroup or legitimize their positions and status in the negotiations.

Since 2013, the search for peace in South Sudan has been scuttled by spoiler activities. In 2016, attempts to consolidate peace in South Sudan failed after fresh violence erupted between government military forces and rebel groups, leading to the collapse of the Agreement on the Resolution of Conflict in South Sudan (ARCSS), signed in September 2015. These battles were instigated by what could be read as continuous disagreement (dogfights) between President Kiir and the then Vice President-designate Riek Machar over the modalities of running the government, as well as principles for pursuing political restructuring in the country.

Between 2017 and 2018, a series of ceasefire agreements were brokered between the government and rebel leaders, most of which lasted mere weeks or months before they were violated. For instance, the Cessation of Hostilities Agreement (CoHA), signed on December 21, 2017, was violated only days after it was signed. Further, in June 2018 after another attempt to end the conflict, a ceasefire was violated just hours after it came into force. Both government and the various opposition factions were blamed for breaking the ceasefire and spoiling peace.

In the current stalemate, however, the question of whether the decision taken by the opposition is a scheme to spoil the peace can be described either as ‘yes’ or ‘no’ depending on the lens of analysis. Starting with the latter, although the opposition asserts that their decision to boycott the formation of the RTGoNU is in the interest of preserving peace in South Sudan, such a step can be interpreted as a ploy to spoil the peace or delay the implementation of the R-ARCSS. Going back to the descriptions of spoiler motivations identified by Newman and Richmond, the recent development could thus be taken as a scheme targeted at increasing the stakes of the opposition in the RTGoNU.

On the contrary, however, the decision taken by the opposition can also be interpreted as a strategy to ensure that mechanisms for the formation of RTGoNU are foregrounded and safeguarded, and a future relapse into war during the transitional period is forestalled. In the official statement issued by SPLM-IO on October 27, the outstanding issues, including, the transitional security arrangements and the agreement on the number and boundary of states, have been described as ‘bare minimums’ and thus must be met before the RTGoNU is formed. As such, the declination by the opposition could be in keeping with the spirit and letter of the R-ARCSS, and as such be appropriate to the need for sustainable peace in South Sudan.

The Pathway to Peace

In light of the above issues, and considering the growing need for sustainable peace in South Sudan, the political leaders must realize the vitality of the RTGoNU as a vehicle that could bring unity and political tolerance in South Sudan. An inclusive government with the full mandate on sustainable security, good and accountable governance, political restructuring and reconstruction, as well as economic transformation, would provide a conducive environment to galvanize peace and procure strong political assurance for the millions of innocent South Sudanese who have suffered gravely from the conflict. While both Kiir and Machar agree to the terms of the R-ARCSS, they should manifest a strong political will and demonstrate willingness to compromise their individual interests for the common good of the people of South Sudan.

The international community should partner with South Sudanese leaders to ensure a joint and complete implementation of the R-ARCSS. Keen attention should be paid to the issues raised by the opposition, as the manner in which they are addressed will either break or compound the ongoing stalemate.

Visiting Juba and bringing the leaders together as was undertaken by the UNSC was a good step toward the unravelling the challenges to the peace deal. The UNSC should refrain from rushing the formation of the RTGoNU and pay more attention to the weight of the outstanding issues, as well as, inter alia, their possible implications to the sustainability of peace in South Sudan. A good suggestion would be to relook the timelines for the R-ARCSS. If, for example, the timelines proved to be unrealistic, then the UNSC, in conjunction with the political leaders, should be open to review these timelines and allow limited additional time for mending the issues before the RTGoNU can be formed. Additionally, the parties to the agreement should be allowed to agree on the number and boundaries of states. This may help to avoid the pitfalls that may arise from a rushed process of implementation, akin to what happened in 2016, when violence re-occurred between state forces and rebel groups.

Notably, the issuance of sanctions and political restrictions against South Sudan’s political leaders, as the United States (US) currently threatens, will do little to bring peace in South Sudan. Instead, the US and other major guaranteeing states should support initiatives that will influence the leaders to voluntarily choose and commit to peace. This could include offering technical and financial support towards promoting security integration as well as building local institutions and structures that will cushion against societal fragmentation during and after the transitional period.

Otieno O. Joel is a Research Assistant at the HORN Institute

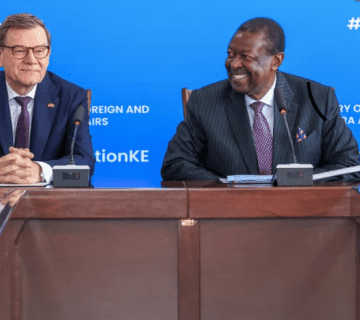

Photo: South Sudan President Salva Kiir at Juba Airport on July 9, 2019 (Photo Credit: CNS photo/Andreea Campeanu, Reuters)