Climate variability and change create extreme weather patterns that result in frequent droughts and floods. Extreme weather and natural disasters have forced millions of people to flee their homes in search of food and pasture in the recent past. The World Health Organization (WHO) estimates that about 47 million people in the Horn of Africa need humanitarian food aid. In Kenya, Somalia, and Ethiopia, the national disasters declared in 2021 are still in effect. Loss of livelihoods; increased concerns over disease outbreaks; destruction of property, and critical infrastructure; population displacement; and rising economic and security risks owing to climate change have also been reported in the three countries. The interaction of these unrelated challenges has created a “polycrisis” (situation in which resolving such crises is difficult) in the region. In Somalia, for example, nearly 7.1 million individuals currently (October 2022) need humanitarian assistance, according to the World Food Programme (WFP). WFP also says drought displaced approximately 1.1 million people from their homes in 2022. It is difficult for Somalia to prioritize climate action in this situation.

Kenya, Somalia, and Ethiopia have action plans and several investments such as Nationally Determined Contributions (NDCs, efforts of countries such as Kenya, Somalia, and Ethiopia that are party to the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change, 2015 Paris Agreement, and the 2005 Kyoto Protocol to reduce GHG emissions) to mitigate climate change. These efforts are, at the least, noble, and the results are mixed. The efforts also attest to varied national priorities and a largely piece-meal approach to complex, cross-border challenges. The three countries can overcome some of the challenges of this approach by exploring ‘Pan-Africanism for climate action’ – operationalized through tripartite climate diplomacy, for instance – to enjoin and integrate their climate change mitigation priorities. This will help Kenya, Somalia, and Ethiopia to build the resilience of their citizens and economies against the adverse effects of climate change faster, and more sustainably. Caution should be exercised to minimize the risk of undermining existing national mitigation priorities though.

Variations in National Mitigation Priorities

The African Development Bank (AfDB) highlights agriculture as Kenya’s largest greenhouse gas (GHG) emitter. Kenya’s annual climate change damages, as captured in the country’s NDC, amount to 3-4 per cent of the country’s USD 110.3 billion GDP. In his remarks at the 27th Conference of Parties (COP 27) in November 2022, President William Ruto said his administration will prioritize resilience, mitigation, and ‘loss and damage’ in climate action through climate finance; introduction of carbon credits (a market-based economic system that incentivizes carbon emission reduction); and increase of Kenya’s forest tree cover by 30 per cent in the next 10 years from the current 12.13 per cent. Kenya’s goals, depicted in her NDC, are to reduce 32 per cent of GHG by 2030; and mainstream sector-specific climate change adaptation and resilience in all sectors, and in county integrated development plans (CIDPs). The country’s top mitigation priorities are expanding the adoption and use of solar, wind, and geothermal power; increasing forest cover; and improving waste management.

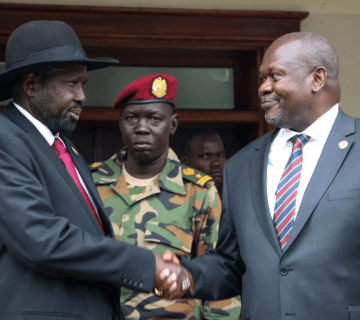

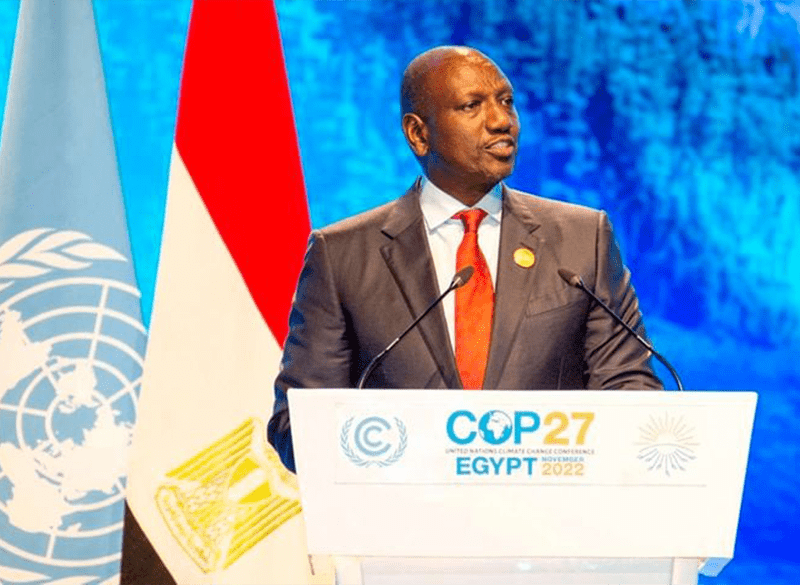

President William Ruto addressing the COP27 meeting in Sharm El-Sheikh, Egypt. (Photo Credit: Nation)

President William Ruto addressing the COP27 meeting in Sharm El-Sheikh, Egypt. (Photo Credit: Nation)

Unlike Kenya, biomass production and use are Somalia’s most significant sources of GHGs, according to AfBD. Somalia, the University of Notre Dame notes, is also the second most vulnerable country to climate change in the world. The country aims to reduce her GHG emissions by 30 per cent by 2030. This is despite Somalia’s contribution of less than 0.03 per cent to global GHG emissions, according to its NDC. Currently, Somalia is prioritizing climate change adaptation over mitigation to enable her citizens to cope with acute famine and drought. During COP 27, Somalia’s President, Hassan Sheikh Mohamud, reportedly said that “… [adaption] requires real resources including accessible grant-based financing and investments in climate resilience in the key areas of water management, infrastructure, and renewable energy.” Somalia has set USD 48.5 billion aside for adaptation. Somalia has also mainstreamed her NDC into her national development goals (NDGs) and employed institutional mechanisms such as the Directorate of Environment and Climate Change (DoECC), National Climate Change Committee (NCCC), and Cross-Sectoral Committee on Climate Change (CSCC) in her climate action. However, some of these are not yet fully operational. Green energy generation, particularly of hydroelectricity and solar energy, is Somalia’s top climate change mitigation priority.

Ethiopia

Like Kenya, agriculture is Ethiopia’s largest GHG contributor, according to AfDB. The World Bank lists Ethiopia among one of the most vulnerable countries in the Horn of Africa to climate change on account of her reliance on rain-fed agriculture, and natural resources, and her “relatively low adaptive capacity to deal with these” anticipated changes. Ethiopia has aligned her NDC to help keep the global temperature rise below 1.5 degrees Celsius. The country also has a Long-Term Low Emission Development Strategy (LT-LEDS) for net zero emissions by 2050. Through its Green Legacy Initiative, Ethiopia plans to increase 30 per cent of forest cover by 2030. Since the initiative’s inception, the country planted 25 billion seedlings. In 2019, Ethiopia planted 350 million trees in one day, breaking a world tree-planting record.

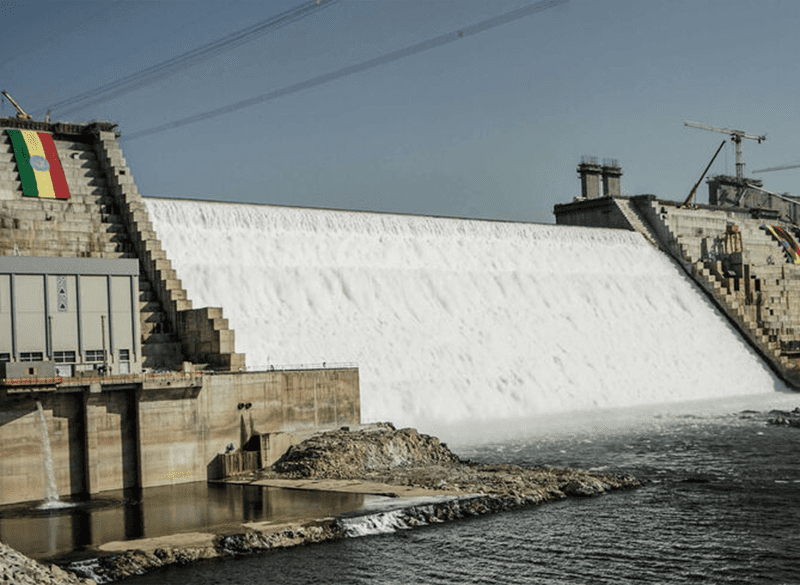

This general view shows the site of the Grand Ethiopian Renaissance Dam in Guba, Ethiopia, Feb. 19, 2022. – Amanuel Sileshi/AFP via Getty Images

This general view shows the site of the Grand Ethiopian Renaissance Dam in Guba, Ethiopia, Feb. 19, 2022. – Amanuel Sileshi/AFP via Getty Images

During his speech at COP 27, Ethiopia’s Prime Minister Abiy Ahmed cited carbon trading as an important source of funding for climate change adaptation. He also highlighted the use of technology to improve food security. He reportedly said “During the dry season, the climate-SMART irrigation system produced approximately 2.5 million tons of wheat. We intend to cultivate 2 million hectares during the dry season alone in 2023, paving the way for food self-sufficiency and wheat export the following year.” Abiy also highlighted the potential of the Grand Ethiopia Renaissance Dam (GERD) to generate more than 5,000 megawatts of electricity when completed and become a vital source of green energy for Ethiopia, and the region. In addition to investing in GERD and other green, renewable energy projects, Ethiopia is increasingly adopting energy-efficient technologies to power her transport, manufacturing, and construction sectors; improve agricultural practices; and rehabilitate land.

Exploring and Enhancing ‘Pan-Africanism for Climate Action’

For reasons that range from governance deficits, and incomplete post-COVID-19 recovery, to national stability, and prolonged drought in the Horn of Africa, financing – one of the “real resources” required to mitigate climate change in the three countries, singly, or collectively – is in short supply. The three countries can explore ‘Pan-Africanism for climate action.’ With the common goals and challenge of reducing GHG emissions by increasing tree cover and adopting green energy options, this action could begin with a tripartite climate diplomacy effort directed at afforestation and renewable energy generation. The management of shared waters and cross-border infrastructure could also be considered. Ethiopia (through the offices of the Africa Union [AU]) and Kenya (through the Committee of African Heads of State and Government on Climate Change [CAHSGCC]), for instance, can mobilize millions of tree seedlings to accelerate afforestation campaigns in the three countries and revitalize Somalia’s ongoing climate adaptation initiative.

President Mohamud and President Ruto assumed power in Somalia and Kenya, on May 23, 2022, and September 13, 2022, respectively. Both are seized on climate action. Working in solidarity to mitigate climate change in the three neighboring countries will allow for more interaction between PM Abiy, Mohamud, and Ruto, strengthening bonds between and among them. Diplomatic engagements to bolster joint climate action could begin with regular consultations and dialogues among the environment ministers or cabinet secretaries of the three countries: Ethiopia’s Minister of Environment, Forest and Climate Change; Somalia’s Minister for Environment and Climate Change, Khadija Mohamed Al-Makhzoumi; and Kenya’s Cabinet Secretary for Environment and Forestry, Soipan Tuya will facilitate the development of a blueprint on joint climate action in the highlighted national priority areas. Such dialogue will also help overcome hurdles associated with ‘loss and damage’ for adverse climatic conditions that are attributable to some of the world’s advanced economies. These inter-state consultative ministerial meetings will be followed by meetings of the three heads of state on the proposed blueprint. These initiatives will set the ground for the 2023 Africa Summit on Climate Change that Ruto, the CAHSGCC Chair, hinted at during COP 27 at Sharm el-Sheikh. Other neighboring countries with similar climate-related challenges in the region and continent could replicate this model to realize their mitigation and/or adaptation priorities.

Renewable sources of energy. Source: ©Mike Fouque – stock.adobe.com

Renewable sources of energy. Source: ©Mike Fouque – stock.adobe.com

This tripartite climate diplomacy will benefit from complementary development partnerships and diaspora support. These can be leveraged to, for instance, help Somalia raise the USD 48.5 billion she needs for adaptation in the short term. Or, as with United States Agency for International Development (USAID) and the National Drought Management Authority (NDMA), for example, to increase the resilience of communities and geographies in Kenya’s Arid and Semi-Arid Land (ASAL) to adverse effects of climate change. ‘Friends of Ethiopia, Kenya, and/or Somalia’ – supported by the African Union, and the Intergovernmental Authority on Development (IGAD), for example – can provide development aid, remittances for climate action, and additional seedlings, for example, in support of Somalia and/or other communities in a similar predicament in the Horn of Africa’s ASAL. These actions may help to resolve the “polycrisis.” Only time will tell.

Asia M. Yusuf is the Strategic Communications Officer, and Roselyne Omondi the Associate Director, Center for Climate Change, Migration, and Development, at the HORN Institute.

A collage of climate and weather-related events: floods, heatwaves, drought, hurricanes, wildfires, and loss of glacial ice. (Credit: NOAA)

The contents of this article are copyright of © The HORN Institute 2022. All rights reserved. Any redistribution or reproduction of part or all of the contents in any form and for whatever reason is prohibited. You may use the content of this article for personal reasons, but acknowledge the author and cite the website as sources of the material.