In the ongoing maritime boundary dispute between Somalia and Kenya over 100,000 square kilometers of maritime territory in the Indian Ocean, Kenya has reiterated its preference for a negotiated settlement and regional dispute resolution mechanisms. This preferred course of dispute resolution heavily depends on Somalia withdrawing the matter from the International Court of Justice (ICJ). However, since 2014, Somalia has displayed consistent reluctance to yield to Kenya’s position, maintaining its faith in the Court and its eventual verdict. In the meantime, Kenya has twice successfully petitioned the Court to postpone the hearing of the matter, from the initial scheduled September 9 to November 6, 2019, and most recently, to June 8, 2020.

Kenya’s out of court overtures

Amid deteriorating relations between Kenya and Somalia, the Ethiopia Prime Minister Abiy Ahmed, intervened to de-escalate the tensions between Nairobi and Mogadishu early this year. The Ethiopian premier and President Mohamed Abdullahi Mohamed (also known as Farmajo) of Somalia, jointly visited Nairobi in March 2019, for a de-escalation and normalization meeting in which Kenya hoped to persuade Somalia to consider out-of-court talks over the maritime dispute. The meeting only resulted in ‘de-escalation’ and ‘normalization’ of Kenya-Somalia relations, and nothing substantive as regards the maritime dispute.

Following the false start for an out-of-court settlement, Kenya is likely to have besought the intervention of the African Union Peace and Security Council (PSC), under Article 7 of the Protocol founding the PSC. In so doing, Kenya might have been guided by various regional resolutions and declarations regarding post-colonial state boundaries and peaceful resolution of disputes in Africa. The respective articles of legal spirit include Resolution 16(1) of the Organization of African Unity of 1964, which preserves colonial boundaries at independence of African states, and Article 4(b) of the Constitutive Act of the African Union of 2002. On the other hand, Resolution CM/Res.1069 (XLIV) of 1986 on peace and security in Africa, as adopted by the 44th Ordinary Session of the Council of Ministers of the OAU, promotes the spirit of negotiated settlement of disputes.

On September 5, 2019, the PSC accordingly issued a communique substantively favoring Kenya’s proposals in the resolution of its dispute with Somalia, for the interest of ‘peace, security, and good neighborliness’ between Kenya and Somalia. The PSC urged both parties to commit to regional dispute resolution mechanisms and alluded to a negotiated settlement to the matter.

Further, on September 24, 2019, the African Union Chairman, also the current Egyptian President, Fattah al Sisi, through his good offices, facilitated a meeting between President Kenyatta of Kenya and President Mohamed of Somalia at the 74th session of the UNGA, in accordance with earlier PSC communique. On September 25, 2019, President Kenyatta made a case at 74th session United Nations General Assembly (UNGA) for an amicable and mutually acceptable settlement mechanism, thereby alluding to negotiated and out-of-Court settlement.

Somalia’s hard-line position

Despite efforts and initiatives at bilateral, regional, and international levels to have Somalia yield to Kenya’s overtures, Mogadishu has stuck to its position on the method of dispute settlement in this maritime dispute with Kenya. In the March 2019 meeting held in Nairobi, the Somalia President remained non-committal to alternative dispute resolution mechanisms as suggested by his Nairobi counterpart. The March repudiation was followed by yet another rejection of out-of-court settlement by Somalia, when Mogadishu faulted the African Union PSC for intervening in a matter already under the judicial process at the ICJ.

Lastly, on September 26, 2019, the Somalia President reiterated at the 74th UNGA, that Somalia would respect ICJ’s verdict and that all parties should focus on the judicial process since the Court has established jurisdiction and competence to effectively and conclusively handle the dispute. Somalia rejected attempts to ‘force’ Somalia out of Court and into negotiations over the maritime dispute with Kenya.

Somalia has offered high-level rejection of Kenya’s overtures, with the most recent show of hard-line inclination, coming barely three weeks after the African Union intervention. The same repudiation comes two days after African Union chairman had facilitated a direct meeting between President Mohamed and President Kenyatta, and one day after the Kenyan President had alluded to out of Court settlement at the 74th session of the UNGA. The extent to which Kenya’s overtures are feasible is increasingly limited as the matter nears to the main hearing in June 2020.

Way forward

The feasibility of Kenya persuading Somalia out of Court hangs in the balance or recedes to the lowest imaginable chance. Be that as it may, politics in Somalia and at the international level might change, in a manner which might trap Kenya and Somalia at the Court, or inspire willingness in Mogadishu to reconsider its hard-line position. However, it is important to establish the fact that neither the African Union nor the UNGA might seize a matter already seized by the ICJ, for the sake of the Court’s independence, integrity, and relevance. Being the Court of last resort, the matter’s presence at the Court is a clear demonstration of the fact that alternative settlement mechanisms failed in the first place. Finally, since the Court enjoys compulsory jurisdiction and relevant procedural provisions of the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS) protect Somalia’s case, as long as Somalia still keeps its faith with the Court, Kenya cannot quash the judicial process by withdrawing its participation in the Court at this stage.

It is, therefore, crucial for Kenya to quickly study the dynamics of domestic politics in Somalia and international politics relevant to the dispute and devise strategic instruments for exploitation of respective dynamics to her advantage. Kenya’s recourse to AU and the UNGA, only attracts opposing procedural and jurisdictional technicalities, while the matter pends in Court. However, in the face of increasingly limited possibility of out-of-court mechanisms to resolving the dispute, Kenya should adequately prepare its case to avoid getting caught in the time-space trap.

Edmond J. Pamba is a Research Assistant at the HORN Institute.

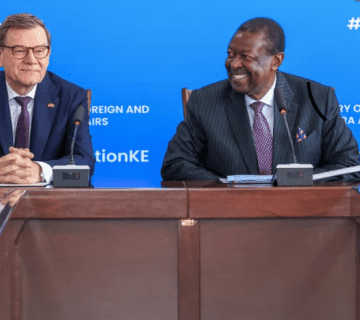

Photo: President Mohamed Abdullahi Mohamed of Somalia (left) and President Uhuru Kenyatta of Kenya during a joint news conference on March 23, 2017 (Photo Credit: VOA)