Only a day after Sudanese women protested their marginalization, and less than a month since Sudan’s Transitional Government (TG) signalled its intentions to cooperate with the International Criminal Court (ICC) over the Court’s possible prosecution of the now-ousted former president, Omar al-Bashir, the new government faced its first big test – an assassination attempt on its leader, Prime Minister Abdalla Hamdok. Hamdok immediately assured the world that the failed coup d’etat that could have derailed his government’s efforts to reinvigorate the inflation-stricken economy, and deliver democracy, has energized the process. “What happened will not stop the path of change, it will be nothing but an additional push in the strong waves of the revolution,” Hamdok said. It is not yet clear the extent to which the coup will impact ‘the path of change,’ but there is little doubt that Hamdok can deliver on this agenda alone. Thus, supporters of democracy – in Sudan, and abroad – must help him to steer Sudan from military to full civilian rule, and keep the state firmly on the civilian rule path.

The idea of civilian rule still sits somewhat uncomfortably with Sudan, as is evidenced by the graduated transition from military rule, through military-civilian administration, to civilian rule over three years, as opposed to a direct military to full civilian transition, for example. This is understandable in a country that has experienced military rule for more than 50 years (collectively). Sudan’s history is also peppered with successful and failed coups. No one has claimed responsibility for the Hamdok assassination attempt yet. However, both the military and Islamists have been involved in previous coups. The April 2019 toppling of former president, Omar al-Bashir, a military ruler backed by Islamists, are two such examples. Fingers may point to possibility that the coup plotters were senior military officers, for several reasons. First, the attempt was bloodless. While at least one vehicle in Hamdok’s convoy was damaged, no one was injured or killed in the attack that has been variously described as ‘a terrorist attack,’ ‘a threat to the Sudanese revolution,’ and ‘an additional push to the wheel of change in Sudan.’ No reports have emerged on the destruction of infrastructure either. Secondly, the coup plotters know that Sudan’s battered economy cannot afford the kind of widespread violence that a successful coup would occasion at this point in the country’s history. Lastly, they also understand that anti-regime protesters are still keen to install democracy in Sudan. Rebel groups, rogue intelligence officers, and allies of Bashir cannot be ruled out though.

Making the Transition

The transitional government plans to cooperate with the Court in ICC’s bid to prosecute Bashir for genocide, war crimes, and crimes against humanity. Additionally, the government is repairing Sudan’s public morality reputation by tackling corruption. These initiatives have earned Hamdok both foes and friends. Support for ICC aggrieves Bashir’s allies who see it as an injustice, and a punishment, but also pleases Sudan’s pro-democracy team. The anti-corruption effort, which has resulted in the dissolution of labour unions, and sentencing of Bashir in December 2019, to two years (imprisonment), is another anger-inducing move for Bashir’s allies. Hamdok can therefore consider the March 9, 2020 attempt at his life as a test of the level of political support for his administration, and the extent to which his removal from office could provoke popular unrest.

The attack that seemed to have called the loyalty of the military into question also revealed support of civilians, and protest groups such as the Forces for the Declaration of Freedom and Change (FDFC), and political parties such as Sudanese Congress Party. The technocrat who leads an 11-person-strong team of six civilians, and five military officers should keep his eyes on the three biggest tasks on his government’s list: rehabilitating the economy; attracting foreign aid and investment; and transitioning Sudan to civilian rule; to keep the ‘wheel of change’ rolling. Hamdok can draw on his economics expertise and experience to deliver on the complex task of improve public morality against the backdrops of capitalism and prevailing market dynamics. In addition to publicly holding corrupt leaders to account, the government should find ways to reduce the runaway inflation that the International Monetary Fund (IMF) now estimates to be at 60 per cent. These include monitoring financial flows in the open and black markets, because illicit funds can frustrate anti-corruption efforts.

Furthermore, it should find ways to gainfully employ the more than 7.5 million unemployed youth. This could be in agriculture, Sudan’s most important economic sector, or the minerals extractions sector, for example. The government can seek the help of her allies to establish more youth-led agri-businesses, or boost exports of agricultural produce to improve the food security of climate-restricted economies, including some Gulf states. Hamdok’s government could also leverage youth unemployment as available and affordable labour to attract the investment of international corporations. This should be done without allowing room for their exploitation. To alleviate economic strain through foreign investment, and improve Sudan’s democracy credentials, Sudan must also negotiate her bilateral and multilateral relations with the West, the Middle East, and the East without allowing potential allies to antagonize each other. Sudan’s request to the US to be expunged from US’s list of terrorism sponsors is a step in the right direction. Stayed on such efforts, Sudan will win more friends than enemies in the military, civilian, and protesters’ camps, and continue to secure the journey to full civilian rule.

Roselyne Omondi is the Associate Director, Research, at the HORN Institute

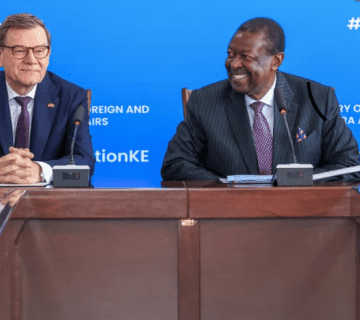

Photo: Security forces inspect a damaged vehicle at the site of an attack on PM Hamdok’s convoy in Khartoum on March 9, 2020 (Photo Credit: AFP)