The March 9, 2020 attack on Sudanese Prime Minister, Abdalla Hamdok’s convoy may be interpreted as an assault on Sudan’s transition process and its nascent institutions. At around 9:05am local time, an explosive went off near Armed Forces Bridge targeting the Prime Minister’s convoy that was heading to Khartoum. Although the Prime Minister escaped unhurt, the act lays open the fragility of Sudan’s transition process that is expected to yield a democratically elected government after 39 months. While the masterminds behind the attack remain unknown – whether supporters of the previous regime or classical terrorists – the direct target of the Prime Minister, who has been leading radical reforms, suggests that the attack was calculated to disrupt the ongoing transition. Therefore, to safeguard the gains made so far in the last six months of the transition, coalition partners – both civilian and military – should rally behind Hamdok’s administration and render full support for the reforms being instituted. The security forces should especially refrain from the temptation to use the attack as a pretext for laying a heavy footprint on the transition.

Sudan began its transition process on August 17, 2019. This was an outcome of a four-month period of on and off negotiations between the civilian opposition, Forces of Freedom and Change (FFC) and the military council that culminated in the signing of the constitutional declaration document and a power-sharing agreement that allowed the formation of a joint civilian-military government. An eleven-member Sovereign Council made up of five representatives, each from the FFC and security forces, and one civilian jointly nominated by both parties, serves as the collective head of state. The Sovereign Council is headed by General Abdel Fattah al-Burhan, who is also in charge of the entire security docket. The Council nominated Abdalla Hamdok – a veteran economist – as the new Prime Minister, who in September 2019, after consultations with the parties, named a cabinet to take over government roles in respective ministries.

Challenges on the Transition

Despite progress in steering the transition, Hamdok’s administration continues to face several internal challenges that may stymie the process of building democratic institutions, and hence, scatter prospects of a successful transition. The major challenge, however, lies in the disintegration among dominant political players. First, the ouster of Omar al-Bashir in April 2019 left behind a wide base of supporters who have harbored negative motives against the ongoing transition and change. These include a group of Islamist political parties and allied security establishment that supported Bashir’s long autocratic rule. Through numerous campaigns, these groups have catalyzed protests and security disruptions aimed at intimidating Hamdok’s government. On January 14, 2020, alongside protests from Bashir supports in Khartoum, a section of the National Intelligence and Security Service (NISS) mutinied against the government, disrupting normal operations in Khartoum and causing the closure of Khartoum airport for nearly six hours.

Second, the apparent imbalance between the civilian and military components of the transition seem to slow down this transition. Although the Prime Minister is responsible for day-to-day running of the government including drafting budgets and managing the civil service, the security forces have maintained their grip on power and continue to use repressive actions. A diverse range of security forces continue to manage the streets, engage in illicit economy and manipulate their civilian counterparts, taking advantage of external support from Gulf Partners, mainly, Saudi Arabia, and United Arab Emirates. A recent stroke in the mounting disharmony came after a secret meeting between the head of the Sovereign Council General al-Burhan and Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu in Entebbe, Uganda in a bid to normalize relations between the two countries. The government of Sudan and allied political parties rejected the meeting terming it a betrayal and sharp clash with the transitional constitutional situation. However, the meeting is alleged to have been initiated by Trump’s administration in its bid to galvanize support for the US’s Middle East Peace Plan which has received a stern rejection from the Palestinian leadership.

Third, the activity of the Rapid Support Forces (RSF), a paramilitary group led by General Muhamad Hamda Dagalo “Hemedti”, who is a strongman in Sudan. Through his forces, the RSF, Hemedti has seized major goldmines in Darfur, South Kordofan and several other places in Sudan, making him a key player in Sudan’s largest export industry. Despite the transitional government’s efforts to reclaim parts of the goldmines, Hemedti and RSF remain in control of large swathes which essentially impede the implementation of Hamdok-led economic reform agenda. RSF soldiers were also linked to the June 3, 2019 Khartoum massacre that left about 100 civilian protestors dead. These actions have cast a general cloud of doubt, questioning RSF and Hemedti’s commitment to the transitional process, and more fundamentally, towards delivering a democratic government in 2022.

Pushing forward the Reform Agenda

Since Prime Minister Hamdok’s take-over of leadership, positive reforms have been witnessed in Sudan. On November 29, Prime Minister Hamdok oversaw the repeal of the repressive Public Order Law that uniquely targeted women for a litany of infractions such as wearing trousers, dancing and mingling with men. Hamdok has also spearheaded internal negotiations with armed groups operating in Darfur, South Kordofan and Blue Nile regions as a way of consolidating peace and internal stability which is set to allow economic take-off. Externally, Hamdok has sought to open Sudan’s borders. In November, the United States of America (US) removed Sudan from the list of ‘countries of particular concerns’.

Along with the need to institute economic reforms, Prime Minister Hamdok has taken substantive steps in negotiating Sudan’s pariah status (state sponsor of terrorism) with the US government. Despite the ouster of Bashir almost a year ago, the designation remains, hampering Sudan’s access to loans from international financial institutions as well as blocking investments from international companies. As such the Prime Ministers’ move to normalize relations with the US after decades of damaged relationships, and purportedly accepting to bear responsibility for the actions of the previous government is an earnest effort to change Khartoum’s foreign policy framework.

Given the foregoing, it is imperative to note that Sudan’s transitional process bears great hope for millions of Sudanese who have gone through difficult socio-economic and political challenges over the last 30 years of Bashir’s rule. With Prime Minister Hamdok bound to face numerous challenges to his ‘wheel of Change’, the benefits of a successful transition are potentially enormous. As such, the transitional government should put in place measures that will strengthen its resilience against internal and external challenges. For instance, as a remedy to the internal security imbalances, the government should pursue measure that will seek for the integration of its varied security forces into one national army. This will ensure uniformity in the national security landscape with potentiality to inspire peace and stability necessary for the transition. Additionally, the government should adopt robust measures to include security reforms alongside ongoing economic and political reforms. Hamdok should also move swiftly to undercut external influences that seem to destabilize the ongoing transition. Particularly, should the administration take caution with any secret military alliances with external powers.

Otieno O. Joel is a Research Assistant at the HORN Institute.

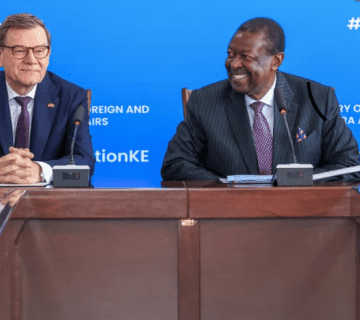

Photo: Sudan’s Prime Minister Abdalla Hamdok during a past press conference. PM Hamdok survived an assassination attempt in Khartoum on March 9, 2020 (Photo Credit: Daily Sabah)