Kenya’s seeming lacklustre responses to the yet-to-be-contained locust invasion, and the potential incidence of COVID-19 in the country has exasperated Kenyans. The exasperation is, in part, result of the undermining of the authority of experts, lack of well-coordinated efforts, and use of double-edged measures that could compound the negative impacts of these two threats in the future. Kenya should consider the potential impact of these bio threats on the country’s food and health securities as national security issues, and respond in ways that inspire Kenyans’ confidence, and ensure their safety and security.

Like some countries in the Horn of Africa, Kenya was paying insufficient attention to the warnings that entomologists were sounding toward the end of 2019 over the impending invasion of desert locusts. The locusts, the Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) noted, were moving from Pakistan to the Horn of Africa region via the Middle East. Kenya, which reportedly experienced its last such invasion more than 70 years ago, was recovering from flooding that had been preceded by prolonged drought at the tail end of 2019, and preoccupied with preventing and/or countering al Shabab activities that increased at the beginning of 2020. Unsurprisingly, the unprepared citizens and the government reacted in unorthodox ways to the arrival of the flying and hopping insects. These included making loud noises, shaking invaded crops, and sending social media images of the locusts to the agriculture ministry. These actions bought the swarms some time, allowing them to decimate more vegetation, and spread to at least 17 counties. Kenya, Ethiopia, and Somalia, are worst affected of the six countries in the greater Horn of Africa region that have been invaded, according to FAO. The locust ‘plague’ will persist for a few more weeks amid FAO warnings of more invasions as newly hatched locusts swarm parts of the country and the region a second time in the coming weeks.

In the meantime, the ‘correct’ way to deal with this threat to food and economic securities of hundreds of Kenyans, especially those in the arid and semi-arid regions of the country, remains in a pit between the opinions of experts and lay persons. Experts are divided over how best to control the insects. There are experts who recommend the use of pesticide control on one hand, and those who advocate for ecologically-friendly actions on another. The pesticide team see the method as a way to control the insects and kill their eggs over a large area quickly. Yet this method also introduces toxins to the environment, and interferes with the food chain of flora and fauna. The potential of pesticides to impact the environment negatively is the reason the experts in the other team advocate for control of the locusts using ‘natural’ means to protect birds, other insects such as bees, and soil-dwelling creatures such as ants, and earthworms. Some lay persons have faulted experts for not consulting them in the anti-locust process, and destroying their traditional ‘food.’ Others for whom the insects are harmful pests have chided the government for slow, inappropriate efforts, and for not caring enough about them and their livelihoods. This lack of clarity has impeded decision making, and slowed down anti-locust initiatives at county and national levels.

In the instances when county and national agencies have responded, their effort has largely been uncoordinated. It is still not entirely clear to the masses which agencies are working with the agriculture ministry to manage the current and subsequent invasions, how long the process will last, and what citizens should or should not do to help. More critically, farmers and agro-pastoralists whose crops the locusts have consumed do not know what they should do next. Questions about the impact of the invasion on their livelihoods, the safety of the sprayed soils, the handling of the partly destroyed vegetation, and whether or not the government will compensate them for the losses remain unanswered. With the climate changing in unpredictable ways, there are real concerns that the vegetation and soils will not recover from the invasion sufficiently to sustain food supplies in the counties and region in the coming weeks. The COVID-19 related restrictions on the movement of people and goods to and from certain states threatens to make things worse for the drought-, flood-, locust-, conflict-afflicted greater Horn of Africa region.

It is anticipated that lockdowns that will likely follow the incidence of COVID-19 in the country or region will exacerbate the negative impacts of the invasion. More than 3,000 deaths globally, reduced trade, and lack of supplies have been attributed to COVID-19. In lockdown situations, undestroyed crops will rot in farms, storage, and transit, raising prices of food and attendant services further. The lack of sufficient goods and services that is already being felt around the globe on account of inadequate production in locations such as China, and restrictions on the movement of people to and from affected states will likely raise prices. Raga and te Velde’s report, Economic Vulnerabilities to Health Pandemics, lists Kenya as one of seven countries (alongside Sri Lanka, Philippines, Vietnam, Kazakhstan, Cambodia, and Nepal) “most vulnerable to direct adverse economic losses due to … COVID-19.”

To manage ‘moral panic’ (fear of ‘evil’ threats to wellbeing of society) and reduce the negative impact of the two bio threats on Kenyans and Kenya, existing disaster control mechanisms should be strengthened, in an inclusive manner, to contain the problems without introducing new ones. For instance, the air and soils in areas where pesticide have been sprayed should be detoxified. Similarly, there should be no room for the transmission of COVID-19 during complete containment (quarantine) and self-quarantine. Individuals in such circumstances should be monitored at specific facilities around the clock. The government should also initiate countrywide mass education campaigns to sensitize citizens on the invasion and virus, the potential impact on the two on the economy, and how Kenya will recover from the same.

Roselyne Omondi is the Associate Director, Research, at the HORN Institute

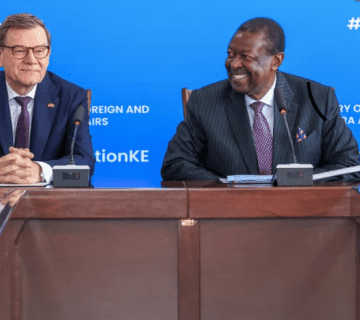

Photo: A local farmer runs through a swarm of desert locusts in Kenya (Photo Credit: ANSA)