The re-establishment of the East African Community (EAC) on July 7, 2000 signaled a new era of cooperation in the East African region. Unlike the previous founding instrument of the EAC that largely focused on cooperation on trade, the existing instrument highlights the intention to integrate its members much more deeply, with the ultimate goal of establishing a regional political federation. The latter entails the merging of the partner states to form a federal state that is governed by a central government. The formation of the political federation is to be preceded by three main stages; the first stage is the establishment of a customs union, the second is the establishment of a common market, the third is the establishment of a monetary union and afterwards the political federation would be formed. Twenty-four years following its re-establishment, the EAC has made commendable progress in the first and the second stages but minimal progress in the last stage. Despite the progress made, the ultimate goal of forming a political federation appears to be elusive owing to the numerous internal wrangles within the community.

Progress made in integration

In 2010, the EAC was able to operationalize a customs union. Key aspects of the customs union include a Common External Tariff (CET) on imports from countries outside the community, duty-free trade between the partner states, and the adoption of common customs procedures. The latter has led to the introduction of the Electronic Single Window System (ESWS) and the Single Customs Territory, developments which have significantly contributed to reduced transit time for goods moving across borders. After operationalization of the customs union, transit time of goods from Mombasa to Kigali was reduced from 21 days to five days. Consequently, the cost of hiring a truck to convey cargo from the aforementioned locations has been reduced by about three-fold.

In the same year (2010), the community established the East African common market with the aim of facilitating the free movement of goods, persons, labor, services and capital alongside the right of establishment and residence among citizens of the member states. As of 2024, the community has largely been able to achieve that, as observed through the use of ID’s and temporary permits as travel documents, alongside the removal of visa and work permit fees for East Africans. Besides that, the community was able to roll out a common East African electronic passport in 2017, signifying a huge step towards integration. The community has further been able to ease communication by establishing a One Network Area (ONA) for both calls and data by the removal of roaming charges in the region. Although the highlighted developments have largely been implemented in the community’s founding member states, the same is not the case for the newly joined member states.

The setting up of a monetary union which is the last stage leading to the formation of the federation has proved to be toughest to accomplish. Key resolutions from the East African Monetary Union (EAMU) Protocol alongside a roadmap which was adopted in 2013 are yet to be implemented. The protocol laid the groundwork for the establishment of a monetary union within 10 years, providing for partner states to progressively converge their currencies into a single currency. Since several partner states were yet to attain the requirements outlined in the EAMU, the deadline for the establishment of the monetary union was moved to 2031.

Internal wrangles within the community

The persistence of internal wrangles within the community has proved to be a great hindrance to cooperation and ultimately the formation of a political federation. Earlier in 2024, Burundi closed its shared border with Rwanda, owing to its accusation that Rwanda was hosting and training the Red Tabara, a rebel group which claimed responsibility for an attack near Burundi’s western border with the DRC. Similarly, DRC has overtime had a strained relationship with Rwanda and Uganda due to sustained claims that the two back the M23 rebel group. Kenya and Tanzania on the other hand, have had recurring disputes, with the recent one being characterized by Kenya’s denial of Tanzania’s request for its cargo flights to enter Kenya, and the consequent retaliatory suspension of Kenya Airways flights into Dar es Salaam. Earlier in 2024, Kenya- DRC relations were put to test when DRC detained a senior official from Kenya’s national airline carrier in the military barracks, under unclear circumstances. The latter was perceived to have a political motive.

The highlighted tensions between the partner states have greatly reduced the probability of forming a federal state. Besides that, the wrangles have impeded free movement of goods, persons and services as envisioned by the treaty of the EAC. It’s worth noting that strained relations between partner states previously led to the collapse of the EAC in 1977. Although the possibility of dissolving the EAC is slim, internal wrangles, if left unresolved, will continue to hinder the community’s efficiency and ability to form political federation.

Is there hope?

The formation of a political federation under EAC remains elusive. The numerous internal wrangles in the community have reduced the probability of partner states agreeing to cede a great amount of their sovereignty to a central government. In 2017, in response to the delayed formation of the political federation, the EAC summit switched to a political confederation as a transitional model. In the confederation model, common institutions and policies in agreed sectors (such as trade, foreign policy, defense and security) will exist although a federal state will not be formed. If subjected to proper public awareness, the confederation model could attract a strong political will. As observed through the Monrovia and Casablanca factions that emerged during the post-colonial era, a majority of African countries treasure their national sovereignty, a factor that is safeguarded in the confederation model. The EAC might therefore want to consider the permanent adoption of the political confederation model as the ultimate goal.

For efficiency in whatever model the community will adopt, the EAC needs to be intentional with resolving internal wrangles. The EAC can consider expanding the mandate of the East African Court of Justice (EACJ) to include solving inter-state disputes. A sovereign adjudicating body reduces the need for employing retaliatory tactics such as closure of borders and banning of flights, which roll back the gains that the community has made.

Jeremy Oronje is a Research Intern at the Horn Institute

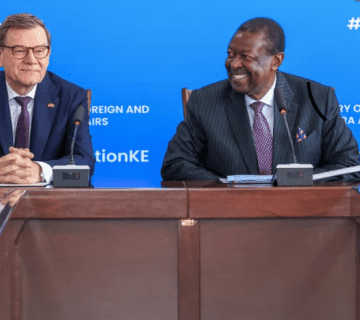

Photo Credits: East African Community

The views expressed in this article are those of the authors and they do not necessarily reflect the position of the HORN Institute.